Melissa Cline and JIll Holdren

April 14, 2022

DNA is, as we’ve all heard, the building block of life. Our DNA helps determine what we look like, how we behave, and what we like to eat. It also contains information about where we came from and what risks or protections we have to health and disease. Until recently, we could only guess at the secrets contained in our DNA.

We are now in an age when we have increasing access to technologies that can uncover some of the complicated variations in our genetic code that help make us who we are, and also perhaps put us at greater–or lesser–risk of disease. It is no surprise that people are flocking in record numbers to get genetic testing.

But as we enter this new world of exploring our DNA, it’s critical for all of us to understand that not all genetic testing is created equal. The type of genetic test you should choose depends on what information you need and want.

There are now several different types of genetic tests available, which can be confusing. In this article, we outline important differences between two main types of genetic tests: the clinical tests available through medical providers and some online labs, and the popular direct-to- consumer (DTC) tests sold by companies including 23andMe, Familytree, and Ancestry. For a quick overview, see the at-a-glance chart farther down on this page.

Clinical Genetic Testing Using DNA Sequencing

Clinical genetic tests use DNA sequencing to look for genetic variation in genes that are associated with increased risk for diseases such as breast cancer. In the past, genetic testing for increased cancer risk often looked at only two genes: BRCA1 and BRCA2. Today, unless you are being tested for a specific gene variant that has already been identified in your family, you will typically receive a panel test, which looks at many cancer-associated genes (FORCE has a good list of the most common cancer-associated genes here)

Clinical genetic tests have one purpose – to detect harmful genetic variation in the genes they look at– and they do this very well. DNA sequencing is highly accurate, and generally can detect any variant in any of the genes in the gene panel, whether or not that variant has been seen before. Clinical genetic testing is the only type of test that can accurately determine if you have inherited an increased risk for cancer (or various other genetic conditions).

Direct-to-Consumer Non-Clinical or Ancestry/health Traits-related Testing

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) tests from ancestry or health traits companies use a different technology, called SNP chips or genotyping arrays. This technology looks for the presence of well-known genetic variants at specific locations throughout the genome. Compared to DNA sequencing, SNP chips are inexpensive. They work fine for detecting genetic variants that are fairly common in the population, such as those related to your physical characteristics or your ancestry. Unfortunately, they are not effective at finding the rare genetic variants that increase the risk of disease.

Even though these tests should not be used to assess your genetic risk of disease, they are fine tests for understanding what your genetics tell you about your ancestry, and, to a lesser extent, basic physical traits. Some reasonable uses of DTC tests include the following:

These test results can be interesting and informative but are not ones that should be used to manage your health in any way. For more information on best practices for using DTC test results, see this practice pointer.

Comparing Results from The Two Genetic Test Types

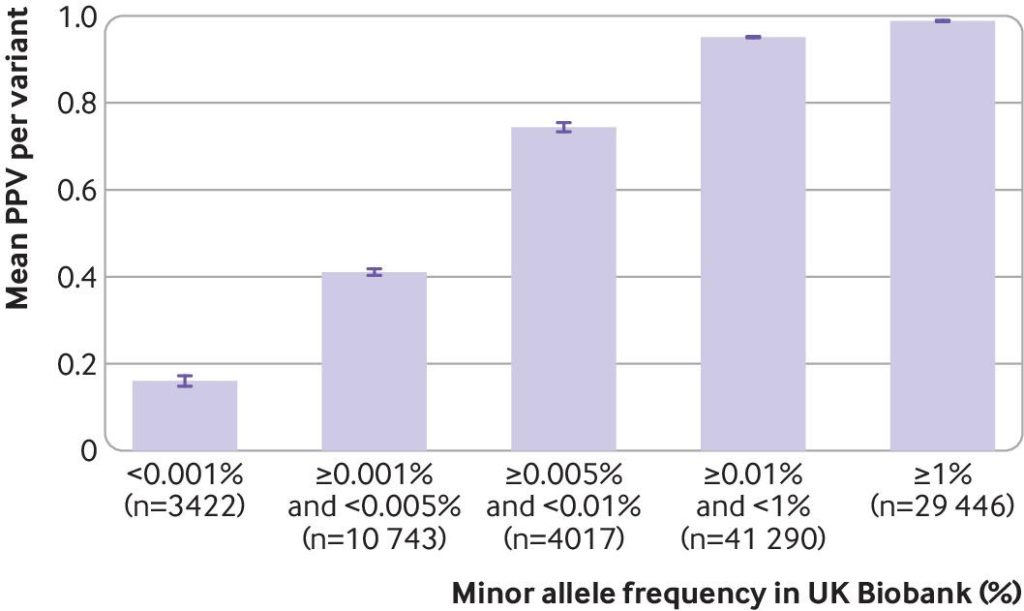

In this excellent article, Caroline Wright and colleagues describe what happened when both kinds of tests were given to the same people.. Figure 1 shows their main finding: SNP chips (the technology used by companies like Ancestry and 23andMe) identify common variants accurately. But for rare variants, like most disease-causing variants, they are not accurate at all. Instead, SNP chips identify a lot of false positives when looking at rare variants, meaning that many people who are told they have a variant of concern do not actually have that variant at all.

Figure 1: The Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of SNP chips at detecting rare variants as a function of the frequency of the variant in the population. The PPV represents the ratio of true positives to all positives (true plus false positives) for the SNPs identified by the SNP chip, divided into bins by population frequency. Most disease-causing variants are very rare, and would fall in the leftmost bin. SNP chips should not be used to assess the genetic risk of disease. Source: “Use of SNP chips to detect rare pathogenic variants: retrospective, population based diagnostic evaluation”, Weedon et al, BMJ 2021; 372 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n214.

A (Partial) Exception to the Rule: Ashkenazi Founder BRCA Variants

In general, disease-causing variants are rare, and rare variants cannot be detected accurately by SNP chips, the technology used by commercial ancestry-type sites online. But there are a few variants that are known to cause disease and are common enough to be detected accurately by SNP chips. These include the three Ashkenazi Jewish “founder variants (or mutations)”. Because the Ashkenazi Jewish population has gone through times when a large proportion of the population was lost, but many of the survivors carried the same genetic variants by coincidence (or because families survived together), the descendents of these survivors frequently carry these variants that were probably rare in the original population. The Ashkenazi BRCA founder variants occur in around 1 in 40 in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, commonly enough that SNP chips technology can identify them fairly reliably. These variants are tested on the 23andMe SNP chips, and 23andMe is authorized by the FDA to report these results. But it is important to understand that 23and me tests for only three out of tens of thousands of BRCA variants associated with a high genetic risk of breast and ovarian cancer. And, it does not test for any of the other cancer-associated variants we know about in dozens of genes other than BRCA1 and 2. Finally, even if your 23andMe test indicates that you carry one of the three Ashkenazi founder variants that they test for, you should get that result verified with a clinical test, because even common variant calls using SNP chips technology can have a high false positive rate.

1 The Askhenazi BRCA founder variants occur in around 1 in 400 people in the general population.

| A Word of Caution Re. Interpreting Your Raw Data from DTC Ancestry Sites It is possible to download your raw data from a site like 23andme and have it analyzed by a third-party company, which might give you additional results. But these results should not necessarily be trusted. The companies like Ancestry and 23andme that sell SNP chip tests have a lot of experience with their technology, and mostly restrict their reporting to reliable results. Some third-party companies don’t have as much knowledge and are known to report test results that are much more speculative. If you have your SNP chip results analyzed by a third-party company and they report that you’re at greater risk of some disease, you should get these results confirmed with a clinical genetic test before believing that they are true. |

Genetic Testing Options At-A-Glance

Differences in Privacy Protections

| TEST TYPE | PURPOSE | WHEN TO CHOOSE | WHERE TO FIND | PRIVACY + OTHER PROTECTIONS |

| Clinical Testing(DNA Sequencing) | To learn if you inherited an increased risk of cancer or certain other health conditions. | You have a personal or family history of cancer, OR You do not have cancer history but want to learn your inherited risk of cancer or certain other health conditions. | Through your health provider or genetic counselor Through a CLIA- certified online lab. | – Regulated by HIPAA – Genetic info is protected health information and cannot be sold to third parties. – US Federal law provides certain protections around genetic information. Employers with >15 employees can not use genetic info to make job decisions (hiring, firing, promotion), insurers can not charge higher health premiums. – Protections do not extend to life insurance, disability insurance, or long term care insurance. – Consumers should still read privacy policies carefully and exercise judgment with all online labs. – While there is always a risk when sharing genetic information, benefits for clinical genetic testing generally far outweigh risks |

| Ancestry/ Traits(SNP Chips) | To learn about your ancestry and some general physical traits. | You are interested in your ancestry and are not trying to find out about your risk of disease. | Online companies like Ancestry.com and 23andme.com. | – Not regulated by HIPAA. – Each company has own privacy policy, which can change at any time. – May sell data – De-identified data is often not hard to re-identify using other datasets. – There is a small but real risk that genetic information from some such companies could be shared with law enforcement. See this article for more information. |

A final distinction between these two types of tests concerns genetic privacy. In the United States, clinical genetic testing companies are regulated by HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), which restricts most data use and data sharing by such companies to activities that relate to “health care operations” (see this article for further information). While no privacy protections are perfect, clinical labs have much higher levels of protection than non-clinical labs. It is important to read privacy policies carefully and ask questions about data sharing and use even of CLIA-certified online labs before deciding to use them.

Direct-to-consumer ancestry testing companies are not regulated by HIPAA, and although they have their own privacy policies, the industry is largely self-governing. Law enforcement has also successfully used direct-to-consumer ancestry type databases to search for relatives of people who have committed crimes, although different companies have different policies regarding sharing with law enforcement.

If you are concerned about your genetic privacy, before you sign up for a direct-to-consumer genetic test, you should read the company’s privacy policy, ask questions, and think carefully about the possible pros and cons of participation. See this article for further information. We will be covering the larger issue of genetic privacy in a future post.

In Summary

In summary, not all genetic tests are created equal! Different tests provide different information and privacy protections also vary. Specifically,

If you have already had a direct-to-consumer genetic test of any sort and you are concerned about the results, talk to your medical provider.

You can find more resources on these topics and many others on Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered’s website FORCE, including links to peer support networks.

For a more technical version of this blog post with additional information on the two technologies we describe here, visit us at the BRCAExchange Blog. You can also find us on Twitter (@brcaexchange).

Disclaimer: these are the views of the authors, and they do not reflect the views of the University of California or other institutions.