Welcome to the first installment of the BRCA Exchange blog!

Cancer, like facial features, can run in families.

Our genes influence many things about us from what color our eyes are, to the shape of our noses, to our health. Changes to certain genes (also called “variants”, “alterations” or “mutations”) can make people more likely to develop certain diseases, like cancer.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are good examples of this. Everyone has two copies of BRCA1 and two copies of BRCA2. We inherit one copy of each gene from our mother and one copy from our father. These genes help us to repair DNA and prevent tumor growth.

But some people inherit a mutated or broken copy of BRCA1 or BRCA2 from one of their parents. When they do, they are at much higher risk of developing certain cancers than most people. For example, while most women have a 1 in 8 chance of developing breast cancer by the age of 70, that number rises to about 1 in 2 or higher for women who inherit a broken copy of BRCA1 or BRCA2. People with harmful BRCA variants also have higher risks of several other cancers, including prostate cancer in men and pancreatic cancer in both men and women.

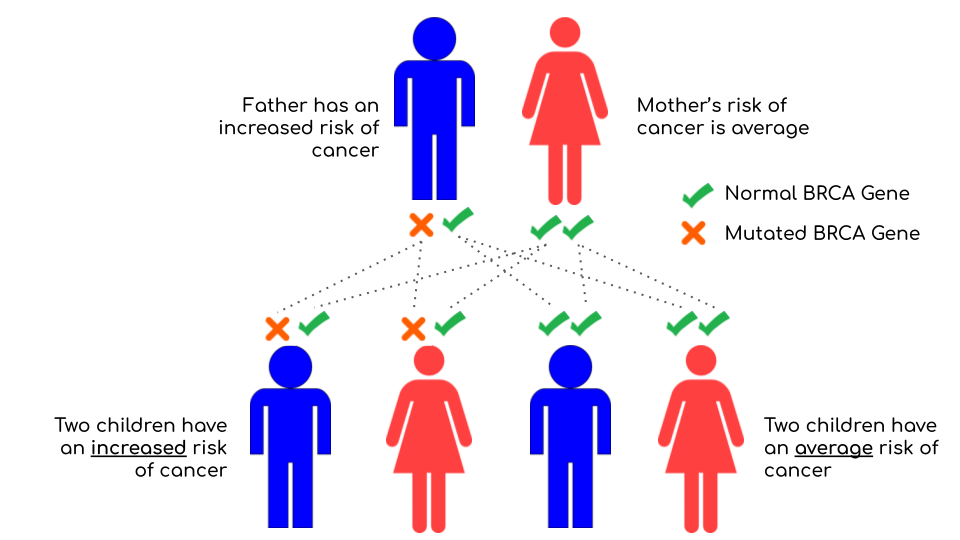

In this illustration, the father carries one mutated copy of the gene, which puts him at increased risk of cancer, while Mom has two normal copies. Everyone inherits one copy of the gene from each parent, and each copy is equally likely to be inherited. This means that the children have a 50% chance of inheriting the father’s increased cancer risk. For male children, this condition would be increased risk of prostate and pancreatic cancer; for female children, it would be increased risk of breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancer. Yes, women can inherit increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers from their fathers!

There are several other genes besides BRCA1 and BRCA2 that are linked to higher cancer risks. For more information about these other genes, please visit the hereditary cancer advocacy group FORCE at https://www.facingourrisk.org/.

Genetic testing can give us important Information about our risks of getting cancer

If people know that they carry a pathogenic BRCA variant or another harmful variant, they can do things to reduce their risk of developing cancer or find cancer in the early stages. But first they need to know that they carry a harmful BRCA variant. The way to find this out is through genetic testing*.

But genetic testing does not always give a clear answer

Changes to genes, or variants, are classified according to how sure scientists are that they are harmful (pathogenic) or not harmful (benign). Table 1 shows the different classifications scientists use when talking about genetic variants.

| Pathogenic | Scientists are quite certain the variant is linked to higher risks of certain cancer |

| Likely Pathogenic | Scientists are not certain but highly confident that the variant is linked to higher risks of certain cancers |

| Variant of Uncertain Significance | Scientists do not have enough information yet to know whether the variant is linked to higher risks of cancer or not. |

| Likely Benign | Scientists are not certain but highly confident that the variant is NOT linked to higher risks of certain cancers |

| Benign | Scientists are quite certain that the variant is NOT linked to higher risks of certain cancers |

There are thousands of BRCA variants that are currently classified as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). These are rare variants and scientists (geneticists) just don’t have enough evidence to figure out whether they increase cancer risk or not.

Partly, this is a data sharing problem.

In general, in order to figure out whether a variant is harmful or not, scientists need some information about the personal or family history of cancer of the people who carry the variant. Since VUS are rare variants, even large genetic testing labs might not see enough examples of patients with the variant to be able to figure out if it is pathogenic (harmful) or benign (not harmful).

The BRCA Exchange is Born

Sharing information between labs would seem like the natural solution, but patient-level information is sensitive and can rarely be shared due to privacy reasons. The Global Alliance for Genomics and Health, an international consortium that seeks to enable responsible data sharing for the benefit of human health, recognized this problem and addressed it by assembling a team of international experts to work together on developing new approaches to share data on BRCA variants while safeguarding patient privacy. The result was BRCA Exchange.

Today, BRCA Exchange shares data on BRCA variants from patient populations around the world, as well as variant interpretation resources selected by the ENIGMA Consortium, the international expert body on BRCA variant interpretation. The website is visited by more than 3000 different users per month from around the world, from countries including Italy, China and France.

Through working with patient communities, we’ve become passionate about education, and that’s what inspired this blog. Over these next months, we look forward to writing articles on frequent questions such as how variants are interpreted, and what all of that stuff on BRCA Exchange means! Through our Investigator Spotlights, you’ll meet some of the people behind BRCA Exchange. And through our Variant Spotlights, you’ll learn what the data on BRCA Exchange can tell you about some interesting variants.. We are also thinking about hosting some live Q&A sessions on Twitter – let us know if you would be interested.

If you have any topics you’d like to learn more about, we welcome suggestions!

*Not all genetic tests are created equal. Clinical genetic tests such as those ordered by your doctor, will assess your genetic risk of certain diseases but will not usually provide information on your ancestry or personal traits. Direct-to-consumer tests such as those by Ancestry.com or 23andMe will provide you with good information on your genetic ancestry, and on personal traits such as the likely color of your hair, but do not provide much information on your genetic risk of disease. We will write more about this in a future blog post.